Roads

Following Penn, Court Orders were issued to require landowners “to make good and passable ways” for neighbors to use. Eventually, these developed into roads. For Chester County, the most important was from Philadelphia to Marlborough Village, laid out about 1704. It was called Marlborough Street Road, but eventually shortened to “Street Road” (Route 926). So important was this road to the development of Pennsylvania that it has been called “the springboard to the west” for emigrants moving inland.

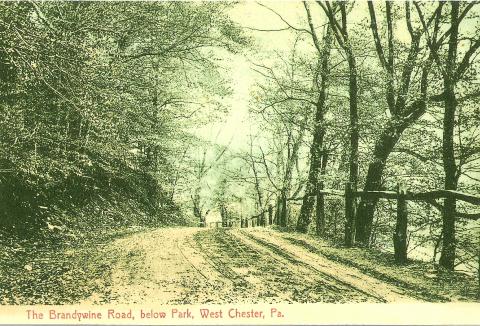

Problems in getting from place to place by the primitive roads of the times were common in latter half of the 19th Century. For example, locals felt forced to petition for a law which would prohibit all farmers from allowing their cattle to roam freely on the public roads. And during one period of winter thaw, the roads were so deep with mud that a coach, even with its stout horses, took 3 1/2 hours to make the trip from Downingtown to West Chester.

When Pocopson Township was formed, plank roads were the latest in travel technology. The underlying foundation of a plank road was two twin rows of timber (called sleepers, stringers or sills) laid down three or four feet apart for the length of the new road. Planks eight feet long and three inches thick were then laid at right angles to the twin rows. A “turn-out lane” of just dirt, about twelve feet wide, flanked the planks, and deep ditches were dug on either side for drainage. The planks were then covered with an inch of gravel or pebbles.

Township Supervisors expected to get seven or eight years of use out of this road before it had to be replaced. Plank roads were widely used, as opposed to gravel or stone. An 1870 report from the New York Senate stated that “plank roads are a more profitable investment than gravel or stone: they never break up in winter thaws or fall away in spring freshets the way paved roads do.”

But only the most heavily traveled roadway would bear the expense of this sophisticated road-building. Many roads serving the residences and businesses in the township were primitive at best – primarily dirt and gravel. They even prompted resident Thomas D. Taylor to sue Pocopson Township Supervisors George Seeds and James Baily in 1881 for not keeping the roads in proper repair. And a newspaper report some years later urged the Supervisors to make a visit to the road near James Baily’s creamery and the sawmill. There they would find that two teams of horses might not be able to pass one another on a dark night. According to this story, one team would surely fall over the embankment and into the millrace.

Township Supervisors were ordered by the courts to erect directional signs, called “fingerboards,” at highway intersections to tell travelers the different localities that the roads led to. But sometimes those travelers depending on these signs to find their way would find instead that the fingerboards had been pushed down or otherwise damaged. (see note on fingerboards shot at by huntsmen)

Then there was the problem at the Wawaset railroad station. Wooden troughs carrying water from a spring to the water tanks would overflow onto the road. The result was mud in the summer and great sheets of ice in the winter.

Bad roads, and the consequent difficulties involved in getting from place to place, prompted one anonymous author to pen this sardonic poem in trochaic meter:

Better roads are coming, boys,

Wait a little longer.

When you’re knee-deep in the mud,

When your horse is done “for good,”

When your patience has withstood

All that Job and family could—

Why, then, maybe you can rest

In the graveyard with the blest.

Better roads are coming, boys,

Wait a little longer.

When the crusher’s teeth are sore,

When your hair and whip you’ve tore,

When your horse will go no more—

Then perhaps you’ll find a road

Leading to the gates of gold.

Better roads are coming, boys,

Wait a little longer.

When the robins nest again,

When the catbird’s on the wing,

When you hear the crocus sing—

When the roads will be so dusty

You’ll call for rain, and that quite lusty.

Better roads became closer to reality as the 20th Century got under way, but the initial impetus came not to make travel easier on the horse, and not to ease the introduction of the horseless carriage.

Instead, the push started with Colonel Albert Augustus Pope, a Union veteran of the Civil War and the manufacturer of a “safety bicycle” in 1878. That machine made bicycling the rage; suddenly, it appeared, both men and women were pedaling out to the countryside on weekend afternoons.

By 1900, over a million bicycles a year were being produced by some 300 companies in the United States, and the ragged state of the existing roads became more and more an issue. Pope moved beyond manufacturing bicycles to consider the road conditions that bicyclists had to put up with. He protested, “American roadways are among the worst in the civilized world, and always have been....I hope to live to see the time when all over our land, our cities, towns, and villages shall be connected by as good roads as can be found.”

Through his efforts, what was perhaps America’s first highway lobbying group, the League of American Wheelmen, was formed; and its Constitution and By-Laws proclaimed, “At each annual meeting of the national assembly at least one day shall be devoted exclusively to the consideration of ways and means for advancing the work for road improvement within the various states...”

The League publication, Good Roads Magazine, supported “good roads” associations across the country and spurred local, state and national legislatures to support road improvements. Within three years, the magazine had a circulation of a million, and groups across the country held road conventions and public demonstrations and published material on the benefits of good roads. New Jersey became the first state to pass an aid bill for road construction in 1891. Two years later, the League persuaded J. Stanley Morton, President Cleveland’s Secretary of Agriculture, to create an Office of Road Inquiry to “furnish information” on road building. Four years later, that Office was furnishing “object lesson roads,” and “Good Roads Days” were held to show neighboring farmers what it would be like to travel on these short sections of well-constructed pavement.

The League also financed courses in road engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and built a short stretch of macadam road in Boston to demonstrate to riders how smooth a ride that could provide. As a side note, the first macadam roads (named for the Scotsman John Loudon McAdam) were not what we would recognize today. The basic construction was three layers of stones laid on a sloped subgrade with side ditches for drainage. The first two layers, totaling 8 inches thick, consisted of 3-inch stones, compacted with a heavy roller. The final layer, about 2 inches thick, was made up of 1-inch stones. What resulted was a strong and free-draining pavement. The first American macadam road was completed in 1823 as part of the “Boonesborough Turnpike Road” between Hagerstown and Boonsboro, Maryland.

That road construction proved useful when the primary traffic consisted of horses and bicycles. But the increasing prevalence of the automobile, at the turn of the 20th century, caused a problem, as the passage of faster-moving vehicles over the surface raised unpleasant clouds of dust, and even began to loosen the packed surface of stones. This problem was rectified by spraying tar on the surface to create “tar-bound macadam” (tarmac).

In 1903, the Pennsylvania legislature, with the backing of Governor Pennypacker, passed an act organizing the State Highway Department. This law was intended to provide help to townships and counties for road improvements.

Perhaps encouraged by the prospect of state aid, the supervisors of Pocopson, East Bradford, Newlin and East Marlborough joined in a common effort to have a continuous stone road from West Chester to Kennett Square via Seed’s Bridge, Unionville, Mine House and Willowdale. A newspaper report of the time promised, “The time is not far distant when all the roads in the county will be linked together, finely graded and stoned.”

But the state aid had its financial limits. Within three years, State Highway Commissioner Hunter was warning that contract awards for more stoned roads in Pennsylvania would be halted for a time because of shortage of funds. Two years later, Commissioner Hunter announced that Chester County had used up its share of state funds for the year well before the year ended.

It wasn’t until 1917 that this road was completed, largely through private subscriptions and township appropriations. Pierre S. duPont, in addition to his substantial help toward other highway improvements in the county, was cited as having contributed $10,000 toward this effort. This local segment, roughly 12,000 feet of roadway in Pocopson Township, was part of the improvement to what was known as the State Road (now route 842), hailed as “a direct thoroughfare to a half-dozen or more of our best-populated towns and villages.”

In 1911, there was a further advance in road construction and maintenance with the passage of the Sproul Act, providing for a state highway system, in which the commonwealth would take over 8,835 miles of existing roads on 296 different routes. Initially, this meant primary highways, but emphasis shifted to farm-to-market roads in the 1930’s. In 1931, 20,156 miles of rural roads, including 593 miles in Chester County, were absorbed into the state highway system. By 1937, the state had taken over roughly 1300 miles of roads in the county, of which about 800 miles had been “improved.”

Activities at the state level did not totally supplant local support of the roads, and “Good Roads Days” continued to attract attention. A newspaper article of the times notes, “The good people of Pocopson are determined to come pretty nigh taking first honors as regard the amount and character of work on the big day. The state highway department will furnish the township with 80 tons of slag, to be moved by volunteer forces on Good Roads Day to that portion of the State road in Pocopson Township leading from John Clark's south to the Carter Farm line.”

But not everybody was happy with the road improvements. R. Smith, President of the Chester Valley Hunt Club, complained that “…the horse is absolutely essential on all farms and in many industries…(but) roads are being repaired, constructed and remodeled with apparent total disregard for the needs of horse traffic.”

Now announcing that the public roads were offered at public sale yesterday afternoon at Corinne. They are selling a length of road for 500 yards to three quarters of a mile. The prices range from $69 to $10. Persons were so generous to the township to take contracts for nothing and present the township with a crisp $10 in cash for the right to control the mending of certain portions of the highway for a period of three years.