Mills of Pocopson Township

The modern reader may well puzzle over the fact that the creek running through much of the township was named after the Indian word pocaupsing, meaning “roaring waters,” because much of today’s Pocopson Creek drifts lazily through the countryside. Nonetheless, during the township’s history, Pocopson Creek provided power for a number of grain and sawmills—starting in the early 1700’s, when Joseph Taylor built a mill there.

That was just the beginning. An 1873 township map in Witmer’s Atlas showed a total of five mills on that creek, and four more close by on other waterways. The Pocopson Mill and William Allcut’s grist and sawmill and woolen factory appeared just off Denton Hollow Road; John Denton’s cotton factory, just north of Route 926; Abner Haines’ grist and sawmill, on Haines Mill Road; and a feed and sawmill, on Route 52 near Locust Grove Road.

Marshall’s grain and sawmill was shown on Northbrook Road at the West Branch of the Brandywine, still within the Pocopson boundaries. Sager’s Mill, at Lenape, was on the Brandywine. Just slightly outside township limits were Marshall Painter’s grist and sawmill in West Bradford on the Radley Run tributary of the West Branch of the Brandywine, and Trimble’s mill on its Broad Run Tributary in Birmingham Township.

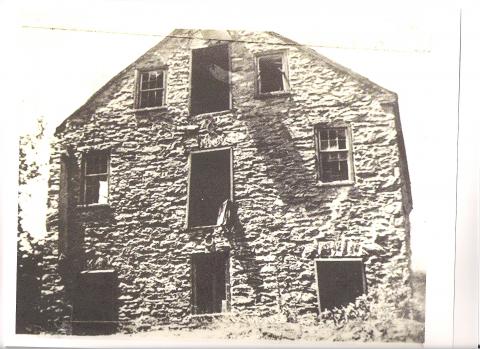

Mill properties also fell victim to the usual hazards. A fire resulting in a $10,000 loss at Pocopson Mills in 1873 was thought to have been caused by lightning. In 1884, Haines’ Mill burned down, apparently because Mr. Henry Haines built a wood fire in the office stove to ward off the chill. The chimney caught fire and the property was destroyed. In 1889, Marshall’s Mill at Northbrook was burned. It was described as a stone structure built in 1796, three stories high and measuring 50 by 80 feet.

A few mills were substantial businesses of the times, according to some newspaper clippings of the 1870’s. The listing for Allcutt’s mill has already been mentioned. An announcement that Pocopson Mills was for sale noted that it consisted of “grist and sawmill, cotton factory, and three dwelling houses, stable and dye house, etc. Ten acres of land. Large lot of machinery in cotton factory, 15 looms, full set of woolen cards, shifting and belting, wooden mule, picker, shearer and folder, water wheel, governor, beaming frame, boiler, three large vats, 40 sets reads and headles, many other articles.”

A miller was very important in these villages. He has been called “host to the entire countryside, an early American politician and the New World’s first captain of industry.” He rarely was paid directly for his work, since farmers of those times seldom used cash. Instead, he took his payment as a portion of the grain he milled -- typically, three or four quarts of grain per bushel, or one quart of malt per bushel.

For at least the last half of the 19th century, these mills were a great service to the farms in the area. Local farmers needed a place to process their crops, and the poor transportation of the times dictated the need for truly local mills. In addition to milling grain and cutting timber, old-time mills did many other jobs that could be made easier through water power: making salt and bone-meal, axes and barrel-staves, hats and pottery, cider, tobacco, paint and plaster, along with countless other chores.

However, all of these old mills eventually ceased operation, doomed by the combination of progressive farming and modern machinery.